What is your pricing strategy?

BBusiness leaders often answer that question by citing a method such as “charging what the market will bear” or applying a markup to costs. Some leaders emphasize goals such as “profit maximization” and “optimal value extraction.”

These pricing strategies have one thing in common: they are number traps. Each lures you into a never-ending quest for the highest possible short-term prices, usually in a zero-sum game. This is true regardless of whether your method to calculate a price is an advanced proprietary algorithm or simply good old-fashioned “guess-and-adjust.”

Arnab and I have explored how business leaders would benefit from a new definition of pricing strategy, one that escapes the number traps and focuses instead on how pricing can shape a business, a market, and even society. We have redefined pricing strategy as the way you influence how the money flows in your market, to whom, and why.

That empowering definition takes your attention off the mind-numbing numbers and focuses it on the creation and sharing of value. How your company shares value with your customers is a fundamental strategic question, not a narrow mathematical one, because those decisions affect your competitive advantages, reputation, financial performance, financial strength, and your degrees of freedom to seize opportunities.

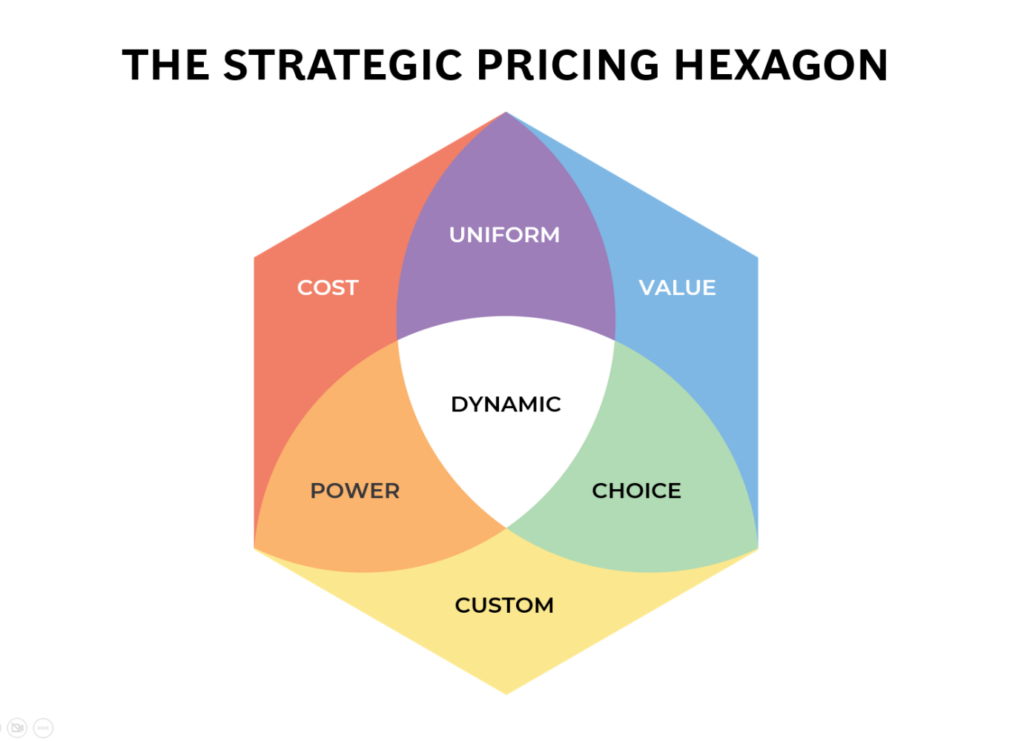

To help you apply that new definition of pricing strategy, we have developed the Strategic Pricing Hexagon, which I introduced in a post a couple of months ago. The Strategic Pricing Hexagon, or “Hex” for short, transforms pricing’s complicated smorgasbord of concepts, theories, equations, and biases into seven pricing games. Each game has its own ideas, rules, habits, and organizational guidelines that will help you shape the future of your market by crafting your pricing strategy efficiently and confidently.

One game should fit your business very well, while most of the others won’t. That is by design. To assume that any pricing strategy, method, or framework – such as price elasticity – is universally applicable or universally necessary is tantamount to saying that playing golf, basketball, soccer, and baseball all demand the same skills and fitness, simply because each sport involves a ball. There are no standard off-the-shelf pricing strategies that you can quickly cut and paste to your own situation.

The three games in the top half of the Hex have familiar names associated with pricing. For decades, they dutifully served companies selling physical products in an analog world, and still represent the best strategic option for some companies. The remaining four games enable companies to win in markets driven either by shorter product life cycles, a proliferation of choices, digital services with negligible marginal costs, and sometimes all three simultaneously.

- Value Game: “Price to value” is a marketing cliché, but this game goes far beyond value-based pricing. Players in the Value Game – such as high tech, luxury goods, and pharma companies – succeed when they align the prices of their unique solutions with customer value, and then obsessively direct their marketing efforts to defend that value and shape demand.

- Uniform Game: Formal education about the mechanics of pricing usually starts with the same “widget” situation: multiple competitors offering one product at one uniform, transparent price to all customers. Players of the Uniform Game – such as consumer goods companies and retailers – win when they optimize the same prices for all customers by carefully weighing the tradeoffs between volume and margin.

- Cost Game: “Never use cost-plus pricing!” is a marketing cliché which insults companies for whom superior cost management is a superpower, not a necessary evil. Players of the Cost Game – such as some industrial suppliers, distributors, and government contractors – succeed when they use greater efficiency to create the degrees of freedom in commoditized markets.

- Power Game: Losing even one major deal can wreck a seller’s business in a market with highly standardized products and a high concentration on both the buyer and seller sides. Players of the Power Game – such as high-tech suppliers – rely on slim advantages to negotiate high-stakes deals that preserve the market’s balance of power.

- Custom Game: This is the polar opposite of the Uniform Game. Players of the Custom Game – which include a wide range of B2B suppliers – win by customizing discounted deals with individual customers amidst heavy competition. The negotiated terms, conditions, and supplemental offerings make each deal unique, even when the underlying products from each supplier seem similar.

- Choice Game: The degree of differentiation in some markets is so high that companies offer a variety of products or services at prices that can differ by an order of magnitude. Players of the Choice Game – an eclectic group which includes software suppliers and some restaurant chains – rely on behavioral economics to help their customers self-select from a well-structured line-up of offerings. How prices compare to each other matters far more than the individual prices themselves.

- Dynamic Game: Imagine that you could share value with any individual customer through optimal price changes in real time by taking costs, competition, customer value, and even strategic and behavioral factors into account. Players of the Dynamic Game – including airlines, sports teams, e-commerce retail, and logistics firms – have begun to apply artificial intelligence together with human judgment to share value with customers in real time in response to supply and demand signals.

Market characteristics and internal capabilities are the strongest indicators that your company may fit to a particular game. But we have also seen companies that have succeeded in an established market by choosing to play a different game from their competitors.

View this edition of The Game Changer Newsletter on LinkedIn