When Apple launched its Vision Pro headset in June, the price point of $3,499 grabbed many of the headlines and sparked countless discussions. Was the price too high? Was it justified? Was it too hard to decide?

For Apple itself, however, the price didn’t warrant a headline. It ended up as a footnote.

Why did Apple bury the price point in a small font size at the end of its detailed 2,300-word description of the new device? The reason is that Apple plays what we refer to as the Value Game.

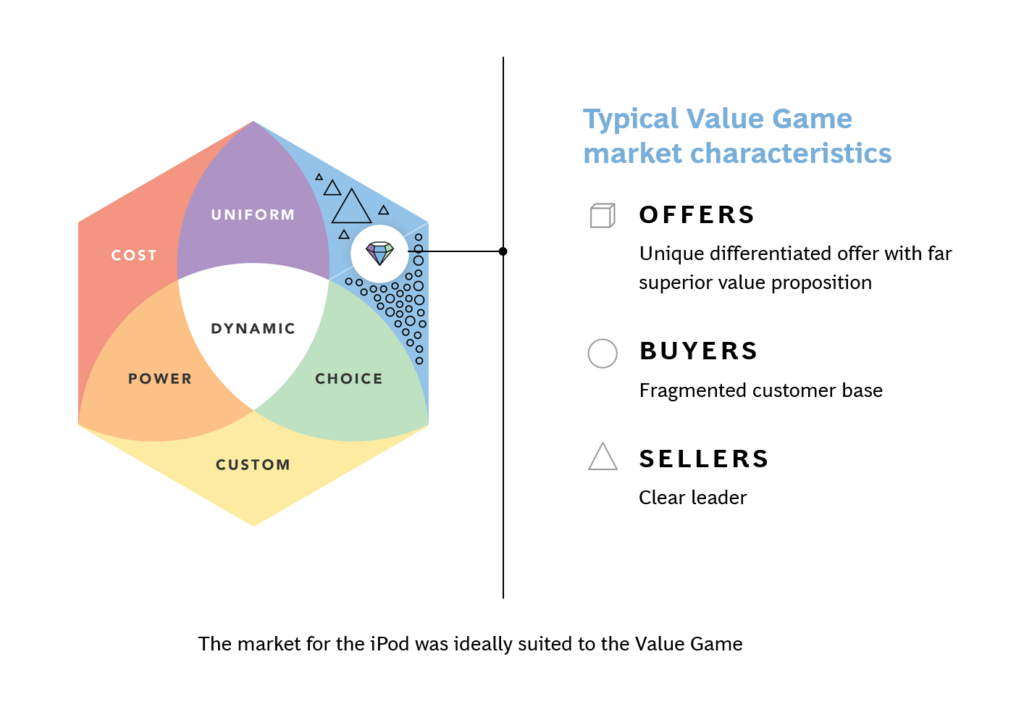

The Value Game is one of the seven distinct pricing games of the Strategic Pricing Hexagon that we introduced in the first edition of our Game Changer newsletter. It stands out from the other games in many ways, but the primary differences are the requisite market characteristics shown in the figure below.

Let’s start with nature of the offers. The common characteristic of luxury goods manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, and many high-tech companies is that they have unique offers with a far superior value proposition. Put another way, the value-in-use of their offerings – whether emotional or economical – far exceeds the value of any direct or indirect alternatives.

In the markets best suited for the Value Game, buyers are so numerous and fragmented that no individual customer or group holds significant purchasing power. Sellers, meanwhile, are few in number, with one company usually the established leader.

This combination of market characteristics gives business leaders many degrees of freedom to set their pricing strategy. We define pricing strategy not in terms of methods and math, but in terms of empowerment: a pricing strategy is a business leader’s conscious decisions on how to shape their market by determining the amount of money available, how that money flows, and to whom.

Prices go beyond the numbers and become marketing messages

Note that Apple expressed the price as one clean amount for one device, uncluttered by fees, discounts, terms, and conditions. This is one way that the Value Game goes far beyond the marketing cliché of value-based pricing. The presumed high amount of usage value, the size of the customer base, and the relative lack of competition for spatial computing gave Apple the ability to treat its launch price point as a product feature and a marketing message that will help it shape demand, not merely respond to it.

Prices in the Value Game are usually not outputs of precise numerical exercises. Tried-and-true pricing frameworks such as price elasticity or cost-plus pricing have no meaningful role to play in helping Apple – or any other players of the Value Game – to find a price that will meet its objectives for sharing value with customers. That’s because a truly breakthrough product has few comparable alternatives, and its value is impossible to assess precisely across a broad spectrum of customers who do not yet know enough about the innovation.

Value anchoring is paramount

Success in Value Game depends not only on aligning prices with customer value and company objectives, but also on anchoring the underlying value. That is why players of the Value Game invest heavily in marketing and innovation. The marketing function exerts the strongest influence on pricing decisions, because of the importance of sustaining the brand value and the pricing latitude that such value creates. Players of the Value Game obsessively direct their marketing efforts to nourish the value perception with arguments that shape the demand. Their investments in innovation, meanwhile, ensure the continuous improvement and the step-change products that keep them a step ahead of customers and competition.

View this edition of The Game Changer Newsletter on LinkedIn