If pricing professionals brainstormed for a slogan to put on mugs and t-shirts, we’re confident that “Never Use Cost-Plus Pricing!” would make their short list.

The critics call out the simplicity of the approach. How can the fusion of only two numbers – a cost and a target margin – possibly serve a company well in the complex economies of the 21st century? They also criticize the fact that neither of those two numbers represents customer value, an omission that borders on heresy in modern marketing.

The players of the Cost Game – including some industrial suppliers, distributors, and government contractors – shrug off those criticisms. These companies constantly strive for greater efficiency in order to create more degrees of freedom in commoditized markets. When they combine this passion for efficiency with the cost-plus pricing approach, they can achieve consistent profitable growth.

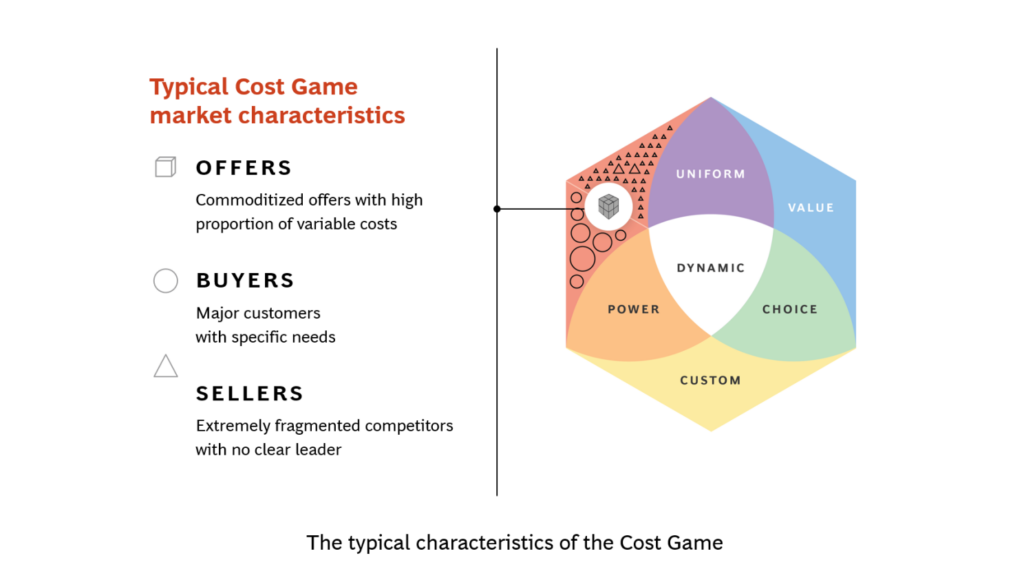

The combination of efficiency and cost-plus works because it fits best to the market characteristics of the Cost Game, as shown in the figure below.

The Cost Game is a natural fit for companies in crowded markets in which products or services have limited differentiation and customers have high bargaining power.

Cost management is their superpower

A customer’s projects in the Cost Game are often defined with so much standardization that those customers, especially governments, can choose a seller primarily based on price. The final product or output is likely to be the same, regardless of seller. Thus, the pricing mechanism in the Cost Game tends to be a simple mark-up of underlying costs. But costs are highly variable and can differ by supplier and by project. For example, construction companies will have different round-trip travel costs, and projects will have different search costs, based on terrain and access. The ability to define, anticipate, and manage costs is paramount. This puts the finance department of the organization in a leadership role for pricing decisions, supported by the other key functions.

But the ”plus” means managing relationships and margins well

Managing costs may be the superpower, but the hidden powers of Cost Game players are relationship and margin management. Customers have significant buying power in these markets, and some of these markets are monopsonies. Automotive suppliers in fragmented supply chains, for example, sell their products to a small number of systems suppliers, perhaps only one. In such cases, relationships can make a difference as the collaborative quest for efficiency over several years can create significant value for the customer and also create and reinforce switching barriers.

Cost Game players often use fees and functional discounts to nudge customers to minimize costs, then share the value of the resulting cost savings with those customers. Companies that excel at the Cost Game also create value by discovering efficiencies across multiple customers.

But the difference between sustained profits and sustained struggles in the Cost Game also hinges on a company’s ability to write and control what we refer to as their margin equation. Their upside in terms of prices is minimal, but their ability to manage costs creates flexibility for them to differentiate their target margins. The more efficiently they can produce their offerings, the greater their degrees of freedom and pricing agency become.

Cost-plus pricing is anything but easy

The definition of cost-plus pricing we gave above – the fusion of only two numbers – is deceptively simple. First, executing this approach requires a company to understand costs in depth. They develop experience, scale, and complexity curves to understand their current and expected fixed and variable costs. Then they optimize all parts of the cost-plus formula. That involves selecting a pricing basis – and often more than one – that aligns with cost drivers and creates a range for margins or “plusses” based on customer and market characteristics.

View this edition of The Game Changer Newsletter on LinkedIn