One of the most enduring clichés in marketing is that “the market sets the price.” Business leaders may feel they lack pricing power in the conventional sense, because they don’t have obvious differentiation or loud competitive advantages.

This is especially true when the market is highly concentrated on both sides. The outcome of every deal matters materially when a limited number of suppliers – each with a portfolio of relatively comparable solutions – battles for business in a relatively open game with a small number of customers who are familiar to all parties.

What matters in those markets, however, is not the exercise of pricing power. It is the maintenance of the balance of power.

That is the essence of the Power Game.

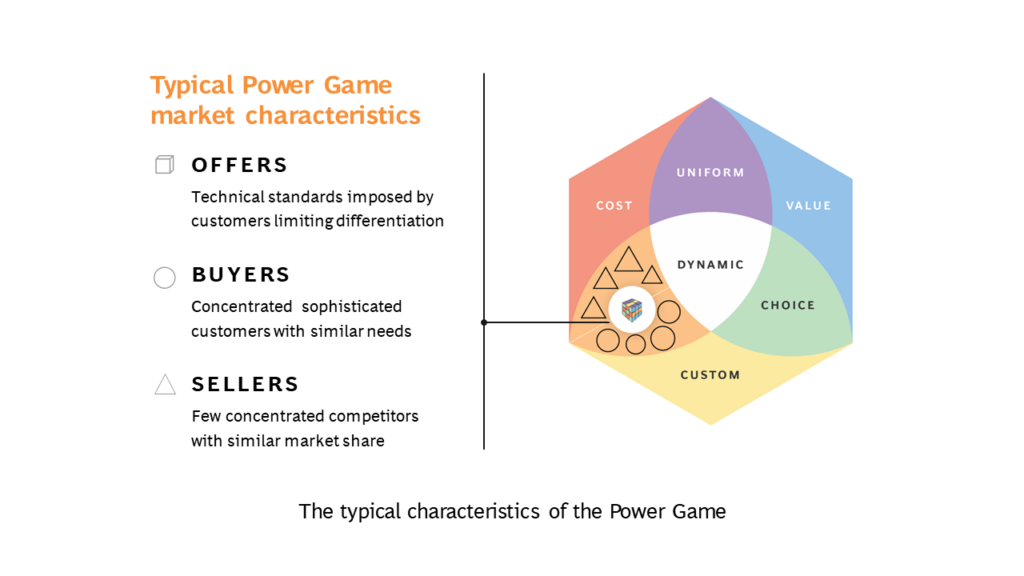

The figure below summarizes the characteristics of markets where the Power Game applies: high or very high concentration on both the buyer and seller sides, and offers that have limited differentiation, usually because buyers impose standards that make offers comparable.

Success in the Power Game depends on a leadership team’s ability to understand and manage fine points of equilibrium in the market. The main pricing framework that governs their decision-making is game theory.

The importance of game theory

The loss of any customer contract in the Power Game will have a significant negative impact on a company’s financial performance. This risk of losing business may compel a company to resort to aggressive discounting to salvage a negotiation, to compensate for a slight product disadvantage, or to make a short-term play to gain share.

The application of game theory serves as a safeguard against this kind of behavior. Players of Power Game conduct high stakes negotiations in a repeated prisoner’s dilemma. With few exceptions – such as strong customer preference, geopolitical interference, or missed product cycles – all suppliers in a Power Game market compete for opportunities on an equal plane.

While individual suppliers – at least superficially – may appear to be fungible, the small cohort of suppliers is anything but fungible. The buyers depend heavily on a small set of suppliers to deliver quality products timely and affordably, but they also depend on them to invest enough to innovate and help the buying companies maintain their own competitive positions with their own customers.

The constant search for an edge

Sellers have an interest in maintaining the integrity of prices across their own portfolio, while at the same time maintaining a balance in the market that is in the mutual interest of both themselves and their customers. To accomplish this, companies need to make unilateral moves to remain compliant with the law.

But the law does not compel any company to make self-destructive unilateral moves. To establish the difference, successful sellers in the Power Game make significant investments to analyze subtle differences across every deal with every buyer. Such imbalances – or what we call advantageous asymmetries – exist in almost every Power Game market and are the only sustainable way to gain share. Share gained through lower prices can only be temporary, because competitors will quickly lower their own prices in response. Time and time again, companies may risk a price war as they try to use lower prices to compensate for product quality weaknesses or product delays. This approach never works in the long term, primarily because lower prices cannot compensate for disadvantages that will ultimately prevent a company from holding any share gains for long in their repeated game.

Managing imbalances in the market

The riskiest behavior for any player in the Power Game is to act as if they have no agency. Getting a fair share of value depends on company’s individual choices, which makes understanding and using agency immensely important. To do this, Power Game players succeed when they:

- Stop seeing their company at the mercy of market forces: Power, stakes, and incentives may seem to be in perfect symmetry across both buyers and suppliers, but that is rarely the case. Companies almost always have some slight advantage that can give them an edge.

- Execute high-stakes negotiations successfully: Sellers evaluate asymmetries based on the different competitive and margin contexts and then game out a targeted negotiation plan that allows them to press their advantages without jeopardizing the balance of power.

- Establish a pricing model that drives efficiencies: Changes to the pricing model, such as customer programs, supply chain support, guarantees, and other incentives can also serve as a vital point of differentiation, especially in the absence of significant performance advantages.

View this edition of The Game Changer Newsletter on LinkedIn