How much is your work worth?

That is the pricing challenge almost everyone confronts personally. The wages people receive are the prices set for their work. That applies to the current tense negotiations between the United Auto Works (UAW) and the car and truck manufacturers in the United States as much as it does to the wage and salary negotiations that will occur in countless companies between now and the end of 2023.

The nature of this pricing challenge is prominent in the work of Harvard Professor Claudia Goldin. She won the 2023 Nobel Prize in economic science this morning for her research into gender differences in labor markets from the 1800’s through the Covid and post-Covid era.

In her 2021 book Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey Toward Equity, Goldin also explored the root causes of disparities between how much men and women earn in today’s labor markets. She frames one of these root causes as a fundamental but often overlooked pricing trend: the price premium paid for what she refers to as “greedy work” versus the discount that employees accept when they work more flexibly. It boils down to the pay difference between the person who remains “on call” primarily for work and the person who remains “on call” primarily for home.

“If we want to eradicate or even narrow the pay gap, we must first plunge deeper toward the root of these setbacks and give the problem a more accurate name: greedy work,” Goldin writes in her book. She credits New York Times correspondent Claire Cain Miller for popularizing that term, which refers to the kind of work that regularly demands long hours and also demands near 24/7 availability of employees, who usually earn outsized rewards in return. Couples have an incentive to specialize, meaning that one spouse takes the “on call” role for work and the other for home. That incentive increases as the value of the “greedy work” increases. Goldin writes:

The greater the hourly wage premium to jobs with long or on-call hours, the greater is the incentive for each member of the couple to specialize, especially if they have children. By “specialize,” I don’t mean that one person washes the dishes while the other dries them. I mean something more pervasive. As we have seen throughout our journey, one person (generally the wife) gives more time to being on call at home, and the other (generally the husband) gives more time to being on call at work.

If the value placed on the greedy work is relatively low, the couple may decide to “effectively purchase couple equity for the amount they forgo from a paycheck. But when the amount is large, the cost of couple equity may be too high to turn down.”

What are Goldin’s solutions? She offers three areas to focus on, only one of which has to do with traditional gender and societal norms. The other two are related to pricing. One is to reduce the cost of workplace flexibility, which requires efforts to “[c]heapen the tradeoff. Make it so that couples don’t have to face as difficult a compromise.” Her other recommendation is to make the tradeoffs for childcare less costly.

How should companies, individuals, and society consider these recommendations and implement them? In the upcoming Game Changer book, my co-author Arnab Sinha and I devote the fourth and final part of the book to “Shaping Society Through Pricing Decisions.” While we only address the links between labor questions and the Strategic Pricing Hexagon in the book’s epilogue, we have two chapters which explore the issues of fairness and equity in pricing, which by extension includes prices in other forms such as wages and salaries. Both fairness and equity defy simple explanations and often lead to counterintuitive outcomes.

Each of our recent newsletters has explored one of the games defined by the Strategic Pricing Hexagon. It is appropriate that today’s newsletter looks in more depth at the Choice Game on the day of the award of the Nobel Prize in economics. Key concepts of behavioral economics play a decisive role in how companies play the Choice Game. Three pioneers in behavioral economics – Herbert Simon (1978), Daniel Kahneman (2002), and Richard Thaler (2017) – have also won the Nobel Prize. Their work, combined with the thinking of many other psychologists and economists, has changed the world’s understanding of how prices influence the behavior of buyers, who do not always make decisions in line with classical economics.

- Winning the Choice Game

Tom Hanks’s character in the 1998 hit movie “You’ve Got Mail” describes what happens when companies make it reflexively easy for customers to distinguish among purchase options and self-select the best one for themselves.

“The whole purpose of places like Starbucks is for people with no decision-making ability whatsoever to make six decisions just to buy one cup of coffee,” says bookstore magnate Joe Fox. In his words, making those decisions rewards the consumer not only with a cup of coffee, but also with “an absolutely defining sense of self.”

Customers constantly face myriad options to buy things, many of which have higher stakes and value than a morning coffee, and many of which also require keen decision-making ability on their part. The ability of sellers to guide customers through these choices in ways that create a mutually beneficial outcome is the essence of the Choice Game.

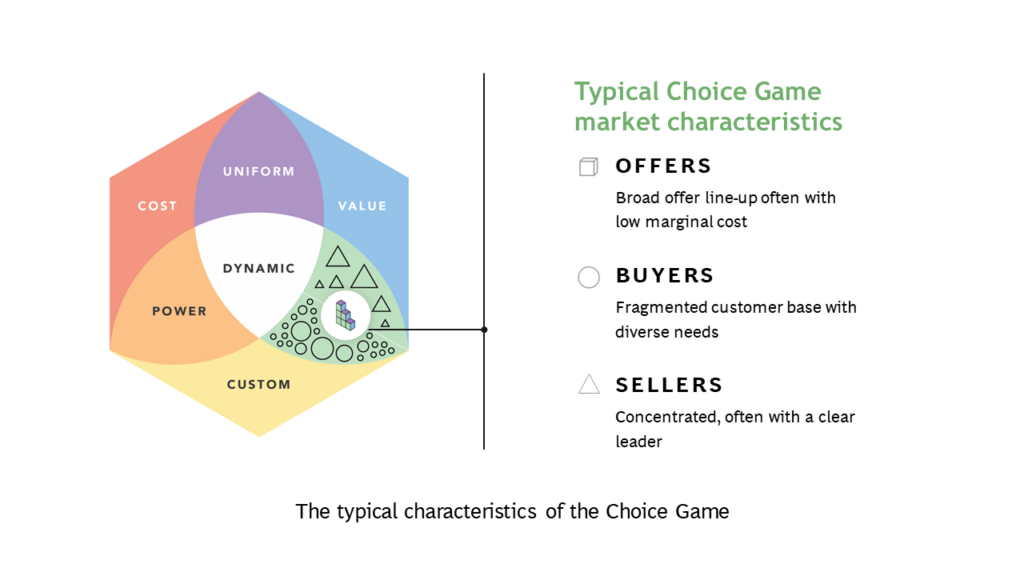

The figure below shows the market characteristics of the Choice Game, which occupies a middle ground in the Hexagon between the chaos of the Custom Game and the focus and clarity of the Value Game.

Like the markets of the Value Game, Choice Game markets tend to be concentrated, often with one clear leader. But unlike the Value Game, companies in the Choice Game aren’t offering a flagship product with a vastly superior value proposition to a large and fragmented market. Instead, they build and maintain a coherent, carefully curated lineup of offerings designed to serve different customer segments defined by their needs and value perceptions. That is also the key difference to the Custom Game, where vast arrays of additional features, terms, and conditions address markets whose customers defy clear segmentation.

The importance of relative price points

If we step back into the conceptual framework that underpins the Hexagon, we see that the Choice Game takes place in markets where value and competition are the primary drivers of strategic pricing decisions, while costs play a lesser role. In many Choice Game markets – such as software and some services – marginal costs are in fact negligible.

Successful players of the Choice Game rely on behavioral economics to help their customers self-select from a well-structured line-up of offerings. They differentiate their prices not only relative to competitors, but also relative to their own products. How prices compare to each other matters far more than the individual prices themselves. The way that the offers are presented – factually and emotionally – influences how customers choose and also incentivizes returning customers to upgrade progressively and choose higher-margin options. We highlight three behavioral effects that play a prominent role in designing and pricing a portfolio in the Choice Game:

- Compromise effect: This means that consumers are more likely to choose the middle option of a set of products over more extreme options. Classical economic theory argues that consumers are rational actors, and thus will choose the option that yields the most value. In practice, however, sellers can expect higher uptake of offerings by juxtaposing them against high-end and low-end offerings.

- Decoy effect: The addition of a decoy option to a portfolio alters customers’ perception of neighboring choices, resulting in a more favorable perception of one of those choices. The imbalance created by a decoy sometimes negates the compromise effect.

- Anchoring: Sellers use this widely studied technique to influence customers’ price perception by carefully determining the first price they see, which then serves as a reference point.

The need for discipline

One challenge in the Choice Game is the ability to keep the portfolio balanced, simple, and fenced. These three elements reflect both the psychological factors mentioned above as well as the ability to renew and refresh the portfolio to keep up with changes in customer perceptions.

Players of the Choice Game can lose their balance and discipline when they design offers that go far beyond what customers need. Sometimes a seller’s motivation is a desire to offer customers more value in absolute terms, while in other cases they want to incorporate a promising new technology before they understand how much value it provides customers. Sellers can also lose balance and discipline when they neglect their segmentation and make too many bespoke offers, as if they were playing the Custom Game. In either case, they undermine the logic behind their portfolio and interfere with customers’ desire to self-select into different packages.

View this edition of The Game Changer Newsletter on LinkedIn